Public School Discipline: Equal Opportunity Offenders

Obama era school discipline policies should be rescinded and replaced with something akin to “best practices” without the threat of punishment or promise of federal goodies.

U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos met with supporters and critics of an Obama-era directive on school discipline on Wednesday. Secretary DeVos is considering changes to the directive and possibly repealing the guidelines outlined therein.

That 2014 directive, issued jointly by the U.S. Departments of Education and Justice, put school districts on notice that they could be found in violation of federal civil rights law if they create and enforce intentionally discriminatory rules. However, and perhaps more importantly, school districts could also be at risk of violating federal civil rights laws if their discipline policies lead to disproportionately higher rates of discipline for students of different racial groups. This risk was present, even if their discipline policies were written without discriminatory intent.

There is an excellent article titled, DeVos Meets With Supporters, Critics of Discipline Rules as GAO Says Racial Disparities Persist written by Evie Blad (@evieblad) covering the meeting and the testimony shared by both proponents and opponents of the directive, over at the Rules for Engagement Blog at Education Week.

Evie writes,

At the heart of the debate of the discipline guidance is why those differing discipline rates occur and the role of the federal government in addressing them. Also at issue: whether schools’ efforts to limit “exclusionary discipline,” such as expulsions and suspensions, have helped students feel more supported or have too severely limited teacher discretion in disciplining students.

She goes on to outline the discipline guidance as follows:

What the Obama-era discipline guidance saysCivil rights guidance cites previous court decisions to clarify for schools and districts what policies and practices could run afoul of federal anti-discrimination laws that relate to issues like race and disability status. Such guidance is not binding like federal law, but it informs schools what could trigger a civil rights investigation from federal agencies.

The discipline guidance says schools’ policies could violate the law if they intentionally treat students differently on the basis of race or if they seem to be written in a neutral fashion but lead to unjustified, disproportionately higher rates of discipline for students in one racial group. That’s a concept called disparate impact, which you can read more about here.

If a school finds black students (or students in any other racial group) in violation of a rule at higher rates than their peers, that rule must be necessary to “meet an important educational goal,” the guidance says. And before settling on a punishment, the school must consider appropriate alternatives that have less of an impact on the disproportionately affected racial group. The guidance’s test for “disparate impact” of a disciplinary policy mirrors the past interpretation of courts in civil rights cases centered on school discipline.

In my view, at all levels of government, our policy approach to discipline should strive for an “equality of opportunity, not equality of outcome”. Regardless of group identity or socio-economic background, students should face the “opportunity for discipline” equally. We should de-emphasize the measurement of outcomes of school discipline policy, as the primary measure of disciplinary policy effectiveness, because it perverts behaviors. If you’re wondering what the impact of this can be, continue reading.

The potential for reward & the threat of punishment, have had a chilling effect on discipline in our public schools. For example, in Broward County where I live and my children attend school, in response to this federal carrot & stick, a “discipline matrix” was developed contemporaneously with The PROMISE Program. Both guide school district officials and their interaction with law enforcement. The stated goal was to reduce the number of Broward County students disciplined for minor infractions and students referred to law enforcement. There is little doubt that the PROMISE Program, and the discipline matrix, were successful at reducing the number of student arrests. In fact, the reduction was significant. The issue is that these programs forced school officials and law enforcement to stay maintain an arms-length relationship and therefore they did not regularly review potential threats to students & staff at schools in the district.

The Rules of Engagement Blog continues,

What critics of the discipline guidance told DeVosCritics say the document has had a chilling effect on local decisionmaking in school discipline.

Racial differences in discipline rates can’t entirely be explained by different treatment in schools, those critics contend. They argue that black students are more likely to be exposed to out-of-school factors, like poverty, which can cause them to misbehave more.

Schools that are afraid of sparking federal investigations have limited teachers’ ability to discipline students without providing useful alternatives, those critics have said. Others, aiming to drive down suspension rates, have set annual goals that some have seen as problematic “quotas.”

To keep discipline rates down, schools either don’t discipline students for some misbehavior or they fudge discipline data in creative ways, Max Eden, a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, said after meeting with DeVos. Teachers are afraid of speaking out about problematic discipline policies for fear of retaliation from their districts or concerns that the media will portray them as uncaring, he said.

Nicole Stewart, a former vice principal at Lincoln High School in San Diego, said she told DeVos about the district’s practice of “blue slipping” students, sending them home with an unexcused absence so their punishment isn’t counted as a suspension. That means counselors and educators don’t always know a student’s full behavioral history, she said.

A student at Stewart’s former school recently brought a knife to school, but because he didn’t brandish it in a threatening manner, he was not referred for an automatic expulsion, she said. Administrators could have recommended him for an expulsion hearing, but they determined his behavior was related to a disability (under separate federal laws, students can’t be disciplined for manifestations of diagnosed disabilities). Two weeks later, the student returned to school with a knife and slashed a peer’s throat in the hallway, Stewart said, retelling a story that was recently covered by the Voice of San Diego. “We are not modeling as a system what consequences look like in the real world,” she said.

The AASA released a more moderate statement following the meeting. Preliminary results of a survey of 850 school leaders in 47 states show that the guidance “has not been transformative in changing discipline policies and practices for districts,” the organization said in a statement. “The claims that it, alone, has transformed districts from safe school environments to unsafe ones is hard to justify. Similarly, our data demonstrate that the guidance has not had a significant effect in reducing out-of-school-time for students or improving racial disproportionality in discipline.” Sixteen percent of districts that have changed discipline practices because of the guidance “have struggled,” the survey found, identifying pushback from parents and teachers, and inadequate funding for student supports as challenges. But “the vast majority” of leaders who said they’ve changed their districts’ discipline practices said they’ve seen payoff from their efforts to review discipline data, provide training and adopt practices like restorative justice and positive behavioral supports, the statement said.

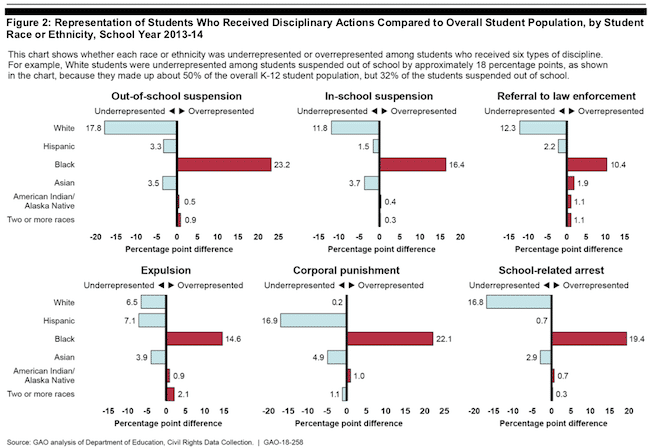

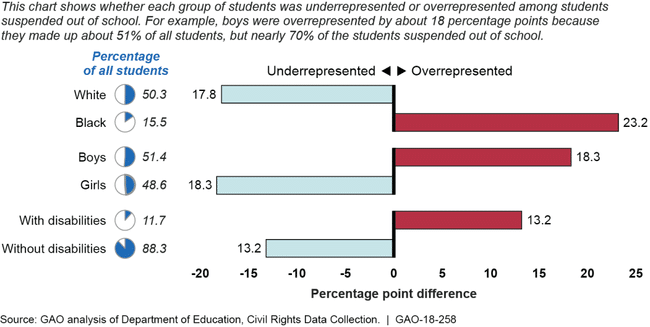

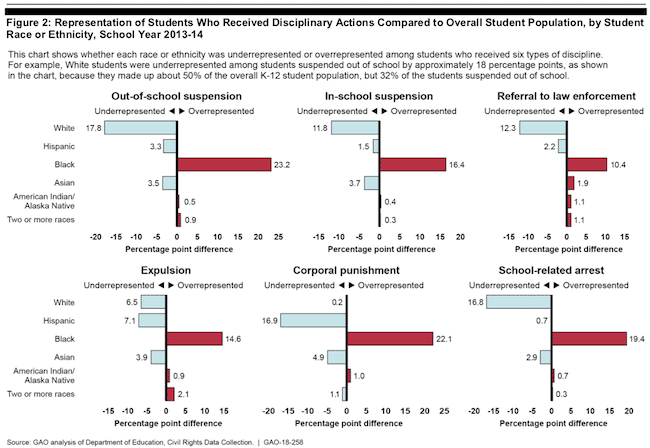

The meetings hosted by Secretary DeVos coincided with the release of an investigation by the Government Accountability Office that found that black students are consistently disciplined at higher rates than their peers. While black students represented 15.5 percent of public school students in 2013-14, they made up 39 percent of students suspended, according to the most recent federal data analyzed in the report.

The GAO Report

The GAO report found disproportionately high rates of discipline for black students, boys & students with disabilities. The report examined six kinds of discipline: in-school suspensions, out-of-school suspensions, corporal punishment, referrals to law enforcement, expulsions, and school-related arrests. It found disparately high rates of discipline for black students across all categories.

The new GAO report included case studies of schools and districts that have been subject to federal investigation for their practices. In The Tupelo Public School District (Tupelo, MS) the GAO found that Black students were disproportionately disciplined in nearly all categories of offenses. These commonly included subjective behaviors like disruption, defiance, disobedience, and “other misbehavior as determined by the administration.” The consequences for “other misbehavior” in high school could be severe, ranging from detention to referral to an alternative school. “For example, among several students who were disciplined for the first offense of using profanity, Black students were the only ones who were suspended from school, while White students received warnings and detention for substantially similar behavior,” the report said.

GAO staff visited a total of 5 districts and 19 schools in California, Georgia, Massachusetts, North Dakota, and Texas. School staff there “reported various challenges with addressing student behavior,” the report says. “They described a range of issues, some complex—such as the effects of poverty and mental health issues. For example, officials in four school districts described a growing trend of behavioral challenges related to mental health and trauma.

The report says the differences in discipline rates cannot be entirely attributed to differential treatment by schools. “Children’s behavior in school may be affected by health and social challenges outside the classroom that tend to be more acute for poor children, including minority children who experience higher rates of poverty,” it says. (emphasis added)

So What Should Secretary DeVos Do?

It would appear that almost all interested parties agree there are external factors that impact the rates of discipline. The outcomes the DoE & DoJ were hoping to improve, have as much as to do with external factors as they do with the policies & implicit bias found in our public schools & our public school personnel. Rates of discipline for various student segments will vary because of these externalities, so why would the DoE & DoJ threaten school districts with lawsuits or reward them grants? DeVos has not committed to a timeframe for a final decision on whether to maintain or amend the current discipline guidance.

In my view, the Obama era rules should be rescinded and replaced with something akin to “best practices” without the threat of punishment or promise of federal goodies. Amending the current guideline is not an option because a simple amendment will create confusion for administrators, teachers, & staff, as well as law enforcement. Furthermore, a new best practice approach should include punishment for any behavior that is criminal–regardless of race, gender, socio-economic status, or any other segmentation. This includes behavior that is threatening to students, faculty & staff. A good rule of thumb: If it would be a felony outside of school, it should be treated as such at school.As we have learned time and again, threats made against a school, students, faculty or staff must be taken seriously and dealt with according to the law–not a policy created by bureaucrats struggling to comply with vague and indiscriminate policy objectives, offers of Federal grants or punitive actions.

The Role of Parents

Often forgotten in the milieu of modern American public education, is the voice of the parent. It is almost always an afterthought & often derided for not having the expertise necessary to weigh in on such matters. It is then no coincidence that I have saved a phrenic nudge of the role of parents until the end. I do so in hopes of elevating the role of the parent in the judgment of the reader.

As parents, it is our sacred duty to ensure the safety of our children and our obligation to see to their education. The state & federal education apparatchik exists only to reassure us in that duty and assist us in that obligation. The holders of positions of responsibility, within the educational system, should be reminded of this from time to time.

As the father who lost a daughter to a senseless act of violence carried out in her school in Parkland, FL, I am living a nightmare created by the evil act of an evil actor. This evil may have been preventable were it not for an amorphous disciplinary climate, created by these misguided federal guidelines & exacerbated by an amoral and ineffective implementation, If these disciplinary policies are not rescinded and significant changes are not made in the way discipline is administered in our schools, Parkland will not be the last incident of mass casualties in a US public school.