Lessons We Should Learn from Averted School Attacks

The latest report from the US Secret Service, Averting Targeted School Violence was released earlier this week. What sets this report apart from previous research done by the Secret Service is a look at attacks that were averted--before tragedy struck.

"Individuals contemplating violence often exhibit observable behaviors, and when community members report these behaviors, the next tragedy can be averted" --James M. Murray – Director, U.S. Secret Service

These words should give us hope. Hope that we can stop the next attack on a school, restaurant, shopping center, or grocery store. The places we share as a community. And, we don't need to give up any of our freedoms to actually be safer.

The latest report from the US Secret Service, Averting Targeted School Violence was released earlier this week. What sets this report apart from previous research done by the Secret Service is a look at targeted school attacks that were averted--before tragedy struck. Let's review some of the key findings.

The U.S. SECRET SERVICE has long held that threat assessment is the best practice for preventing acts of violence directed at the president and other public officials the agency is mandated to protect. Threat assessment is an investigative approach to identifying and intervening with individuals who may pose a risk of causing harm, and the Secret Service considers threat assessment to be as important as the physical security measures the agency employs.

From the report's findings:

Targeted school violence is preventable when communities identify warning signs and intervene.

In every case, tragedy was averted by members of the community coming forward when they observed behaviors that elicited concern.

Schools should seek to intervene with students before their behavior warrants legal consequences.

The primary function of a threat assessment is not criminal investigation or conviction. Communities should strive to identify and intervene with students in distress before their behavior escalates to criminal actions.

Students were most often motivated to plan a school attack because of a grievance with classmates.

Like students who perpetrated school attacks, the plotters in this study were most frequently motivated by interpersonal conflicts with classmates, highlighting a need for student interventions and de-escalation programs targeting such issues.

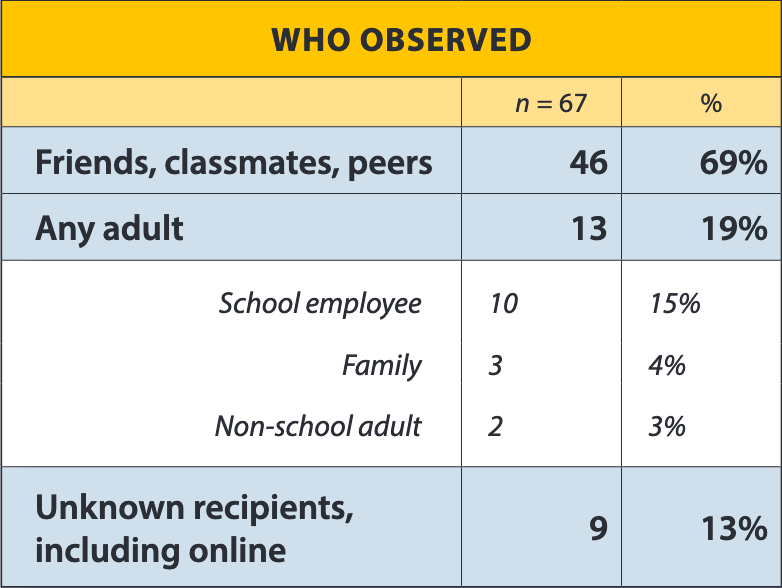

Students are best positioned to identify and report concerning behaviors displayed by their classmates.

In this study, communications made about the attack plot were most often observed by the plotter’s friends, classmates, and peers. Schools and communities must take tangible steps to facilitate student reporting when classmates observe threatening or concerning behaviors. Unfortunately, many cases also involved students observing concerning behaviors and communications without reporting them, highlighting the ongoing need for further resources and training for students.

The role of parents and families in recognizing concerning behavior is critical to prevention.

Eight plots in this study were reported by family members, illustrating the crucial role families can play in addressing a student’s risk of causing harm. In some cases, other parents in the school community received concerning reports about a classmate from their children, then passed the information on to the school or law enforcement. When identifying and assessing concerning student behavior, a collaborative process involving parents or guardians is ideal. Families should be educated on recognizing the warning signs and the supports and resources available to address their concerns, whether in the school or the greater community.

School resource officers (SROs) play an important role in school violence prevention.

In nearly one-third of the cases, an SRO played a role in either reporting the plot or responding to a report made by someone else. In eight cases, it was the SRO who received the initial report of an attack plot from students or others, highlighting their role as a trusted adult within the school community.

Removing a student from school does not eliminate the risk they might pose to themselves or others.

Five plotters in this study were recently former students who had left school within one academic year of the plot, as they had been expelled, enrolled in other schools, graduated, or stopped attending classes. This indicates that simply removing a student from the school, without appropriate supports, may not necessarily remove the risk of harm they pose to themselves or others.

Students displaying an interest in violent or hate-filled topics should elicit immediate assessment and intervention.

Consistent with prior National Threat Assessment Center (NTAC) research studying school attackers, many of the plotters in this study displayed such interest, particularly in the Columbine High School attack. Nearly one-third of the plotters conducted research into prior mass attackers as part of their planning. Nine also displayed interest in Hitler, Nazism, and/or white supremacy.

Many school attack plots were associated with certain dates, particularly in the month of April.

Some plotters selected dates to emulate notorious people or events, such as the anniversary of the Columbine attack on April 20th, while others chose their dates to coincide with the beginning or end of the school year. School and security professionals should approach these dates with extra consideration.

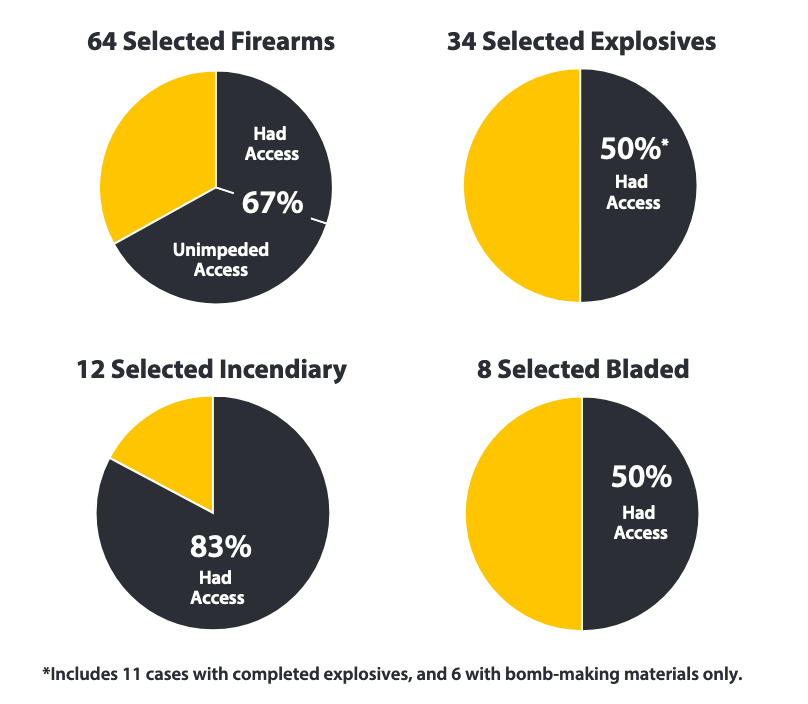

Many of the student plotters had access to weapons, including unimpeded access to firearms.

Threat assessments must examine a student’s access to weapons, particularly those in the home. Similar to school attackers, in most of the cases where plotters intended to use firearms, they had unimpeded access to them (e.g., they owned them or their parents allowed access). In seven cases, the plotters acquired secured firearms because they were given access to the safe, pried the safe open, found the key, or stole them when they were left out.

Why do they do it?

Grievances. For many, retaliating for a grievance played a role in the motivation of the attackers. Many sought revenge for perceived wrongs, grudges, or feelings of resentment. Most frequently, these grievances involved peers. One example,

Two 13-year-old males planned to use firearms and bombs to attack their middle school. The plotters had researched how to build bombs, how to make tear gas, and even practiced making Molotov cocktails. A “kill list” was also drafted by the plotters to “punish” specific classmates and most of the school’s football team. The plotters specifically selected these fellow students because they had subjected the 13-year-olds to years of bullying.

Another example involved grievances around school staff.

An 18-year-old male crafted a plan to detonate pipe bombs at his high school. A few weeks prior to plot discovery, he had been suspended from his high school for making sexual advances toward another student. He planned to “blow [the school] up” because of the disciplinary actions he had received. The plotter was vocal about his grievances, as he directly relayed them to a high school counselor.

Other reasons for the attacks were a desire to kill, suicide, and even fame and notoriety.

A 16-year-old male planned to carry out a Columbine-style attack at his school. The student was depressed and frustrated with his school and felt that others mistreated him. His MySpace username included “TCMI,” which stands for “Trench Coat Mafia International,” a reference to the Columbine shooters. The plotter also ran an online group for members who sympathized with the Columbine shooters. He wrote in his journal that he wanted to carry out a Columbine-style attack at the school, saying “I wanna break the current shooting record. I wanna get instant recognition.”

Planning the Attack

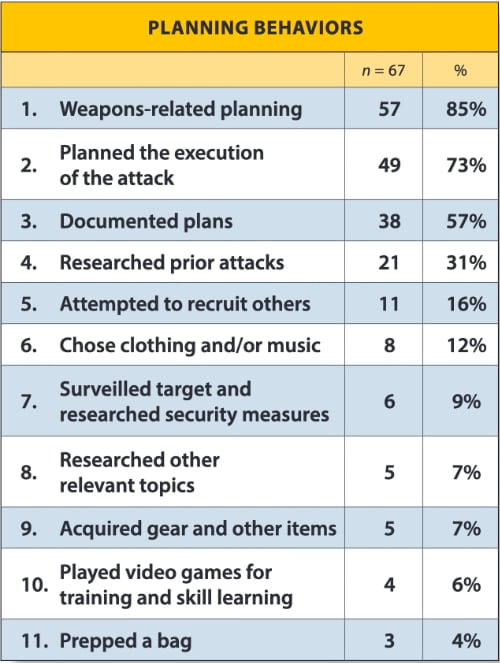

In all 67 cases the report studied, 11 categories of observable planning behaviors were identified. Most of these behaviors are similar to those found in previous Secret Service research.

Plot Elements the Weapons of Choice

Over half of the plotters (55%) chose to use at least two or three types of weapons, while just under half (45%) planned to use just one type of weapon to carry out their attacks. For nearly all of the cases (96%), the weapon(s) of choice included one or more firearms. The second most frequently chosen weapon was explosives (51%), followed by incendiary devices (18%) and bladed weapons (12%).

And herein lies the problem with the gun control narrative in protecting our schools. With 55% of attackers choosing more than one weapon for their attacks, many choosing explosives and incendiary devices, do you still think gun control is the solution?

Plot Detection & Reporting

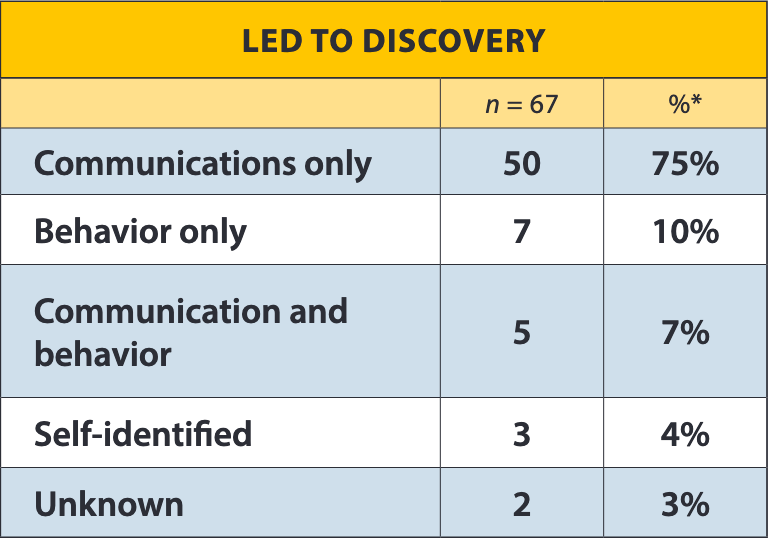

In nearly all (94%) of the cases, the plotters shared their intentions about carrying out an attack targeting the school in various ways, including verbal statements, electronic messaging, and online posts. You read that right--94 percent. If we know about these attacks before they happen, we can stop them. In fact, that is the point of studying these averted attacks. They were stopped before innocent lives were taken.

Implications of Threat Assessment

As I have said before, threat assessment is the best practice for preventing targeted school violence. Time and time again, the research shows that attackers display "concerning behaviors" on the pathway to violence. States, communities and school districts and schools should develop multidisciplinary threat assessment programs. If you are in government, are a school administrator, teacher, counselor, School Resource Officer or a concerned parent, the NTAC guide called Enhancing School Safety, is a great place to start. So is schoolsafety.gov.

When conducted properly, a threat assessment will provide robust intervention and support for students on a pathway to violence.

As the Secret Service report notes: "the primary objective of school threat assessment policy is not to administer discipline or introduce students into the criminal justice system". While discipline and the criminal justice system may be required to prevent tragedy, the "primary objective of a student threat assessment should be providing a student with help and working to ensure positive outcomes for the student and the community".

This analysis of averted school attacks demonstrates that there are almost always intervention points available before a student’s behavior escalates to the point where an arrest may be warranted. These intervention points may include addressing bullying, providing mental health supports, assessing the impact of home-life factors, and mediating conflicts between classmates. A threat assessment program establishes a system for implementing these types of interventions and entrusts a team with responsibility for ensuring that no student falls through the cracks.

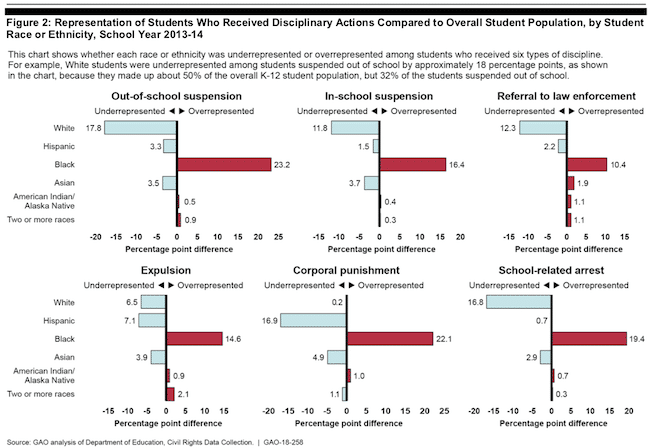

One additional note: In today's hyperpoliticized environment, questions about behavioral threat assessment and its role in school discipline and whether it disproportionately impacts students who belong to minority groups or students with disabilities inevitably arise. Research from the University of Virginia demonstrates that with properly implemented threat assessment programs, there is no disproportionate impact to minority students or students with disabilities. In fact, the study actually found that threat assessment programs reduced the racial disproportionality of suspensions in Virginia schools; "Schools implementing the Virginia model (behavorial threat assessment) tend to have lower suspension rates and, for long-term suspensions, narrower racial discipline gaps".

In 2018, the University of Virginia examined 1,836 threat cases from 779 elementary, middle, and high schools. This study found no statistically significant differences between Black, Hispanic, and White students in regards to school suspensions, and found no racial disparities in the rates of arrests, incarcerations, or legal charges. The study found that only about 1% of students were expelled and only 1% were arrested, even though every threat assessment team incorporated a police officer as a team member.

Conclusion

As our nation continues to struggle with tragic and deadly attacks on our schools, neighborhoods and public spaces, far too many seek safety in gun control measures which have little impact on targeted attacks or more generalized gun violence. The debate over gun control prevents us from implementing solutions that actually work.

As the father of a victim of a targeted attack, I'm often asked, why I don't support common sense "gun safety" or "sensible" gun control. My response is simple. If well-intended gun laws stopped criminals from breaking the law, we would have never seen a child killed in a so-called gun free zone. Criminals don't obey the law--that's why they are criminals.

Instead join me and let's work on preventive methods that address the root causes of violence. Once the first shot is fired, we have lost the battle. Everyone has a role to play in preventing targeted attacks. I want to thank the NTAC team for their research that shows targeted school violence is preventable if those with concerns will share them with authorities who have been appropriately trained to assess the threat and resolve it.