The slow death of DRM

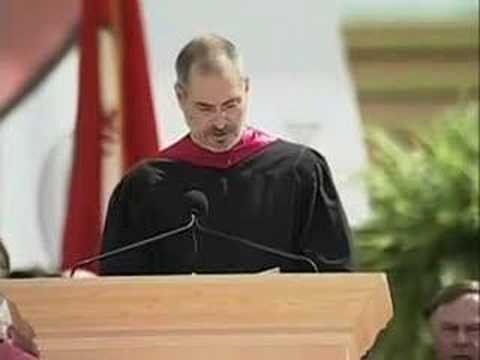

From The Register — According to Steve Gordon, attorney and former Director of Business Affairs, TV and Video at Sony Music for ten years, the DRM walls are crumbling. Earlier this week, Steve Jobs called on the major record labels to allow online music sales unfettered by digital rights management restrictions. Today, EMI is in negotiations with several digital music services to sell unprotected MP3s. Here is the long, sad history of DRM, and why we’re better off without it.

But instead of truly competing with “free,” Sony chose to sue Napster. That strategy lead to the emergence of other P2P services which simply took its place.

Three years later the major labels finally took their first serious stab at competing with P2P by launching MusicNet and Pressplay. But both services were mired by, and ultimately destroyed by, DRM. Neither Pressplay, from Sony and Universal, nor MusicNet, a service from EMI, BMG and Warner, allowed downloads or portability, thanks to DRM. They were stillborn and died quickly.

As an indication of how insignificant authorised digital downloads are to the music business, Apple’s four year slog with its iTunes store has grossed it less than $2bn, whereas gross sales from ringtones were over $6bn worldwide last year alone. And the growth of digital sales is definitely flagging. Although digital sales grew last year, the rate of increase was less than in 2005, and according to Billboard Magazine, in the year to come the US “revenue from digital downloads and mobile content is expected to be flat or, in some cases, decline next year”.

Is DRM to blame? Common sense suggests that DRM is a huge factor in the lack of growth in digital sales. As Steve Jobs correctly points out in his “Thoughts on Music“, the absurdity of DRM is that anyone can now buy a CD, and rip, mix, burn, and upload to their heart’s content.

“So if the music companies are selling over 90 per cent of their music DRM-free,” wrote Jobs, “what benefits do they get from selling the remaining small percentage of their music encumbered with a DRM system? There appear to be none.”

Making consumers pay a comparable price for a digital download, which at 99 cents per single roughly equals what you would pay for a CD, encourages them to steal. People don’t want limits on what they can do with the music, so consumers take the slight risk of an RIAA lawsuit and retaliate by downloading for free. Illegal downloads still outnumber legal by 40 to 1 according to the big label representatives, although insiders put the figure as high as 100 to 1. DRM is not serving these consumers, and that’s how DRM is hurting rather than serving the copyright owners it is meant to protect.